The earliest artistic influence on Diego Rivera was the Madrid academy. Rivera, however, quickly embraced other styles such as Impressionism, Divisionism, the Nabis’ Synthetism inherited from Paul Gauguin, the Primitivism of Douanier Rousseau, Giorgio de Chirico’s geometric handling of space; then, when he met the Parisian Cubists, he was affected by their work from the arliest days of the movement, and he even dabbled in collage. Even in this period, however, he retained a certain sensuality and the authenticity of his ethnic sources, as for instance in his 1915 Landscape in Zapata and The Architect dated about 1916. The works Rivera exhibited from 1906 at the Salon d’Automne clearly reveal these successive influences; especially a Motherhood from this period, now in a collection in Mexico, which is purely Cubist and reminiscent of Francis Picabia’s Procession in Seville or Roger de La Fresnaye’s Conquest of the Air. More accurately José Pierre wrote that Diego Rivera developed ‘a very personal Cubism, austere and solid both in construction and colour, after some excellent work where he was influenced by Cézanne’.

Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 and adopted a Realist style, enhanced by his experience of Cubism. From 1922 onwards he devoted himself to murals, an art form destined to become the most striking manifestation of his talent in the period between the wars. These very large mural paintings show the development of Mexican society after the 1910 revolution with an emphasis on both Mexico’s pre-Columbian past and its modern revolutionary fervour. Rivera rediscovered the art and civilisation of the Mayas and the Aztecs, while not overlooking contemporary history and the revolution. Rejecting most of the influence he had met in Paris, he led the campaign for the creation of a specifically Mexican and revolutionary art school. His enterprise quickly received official backing.

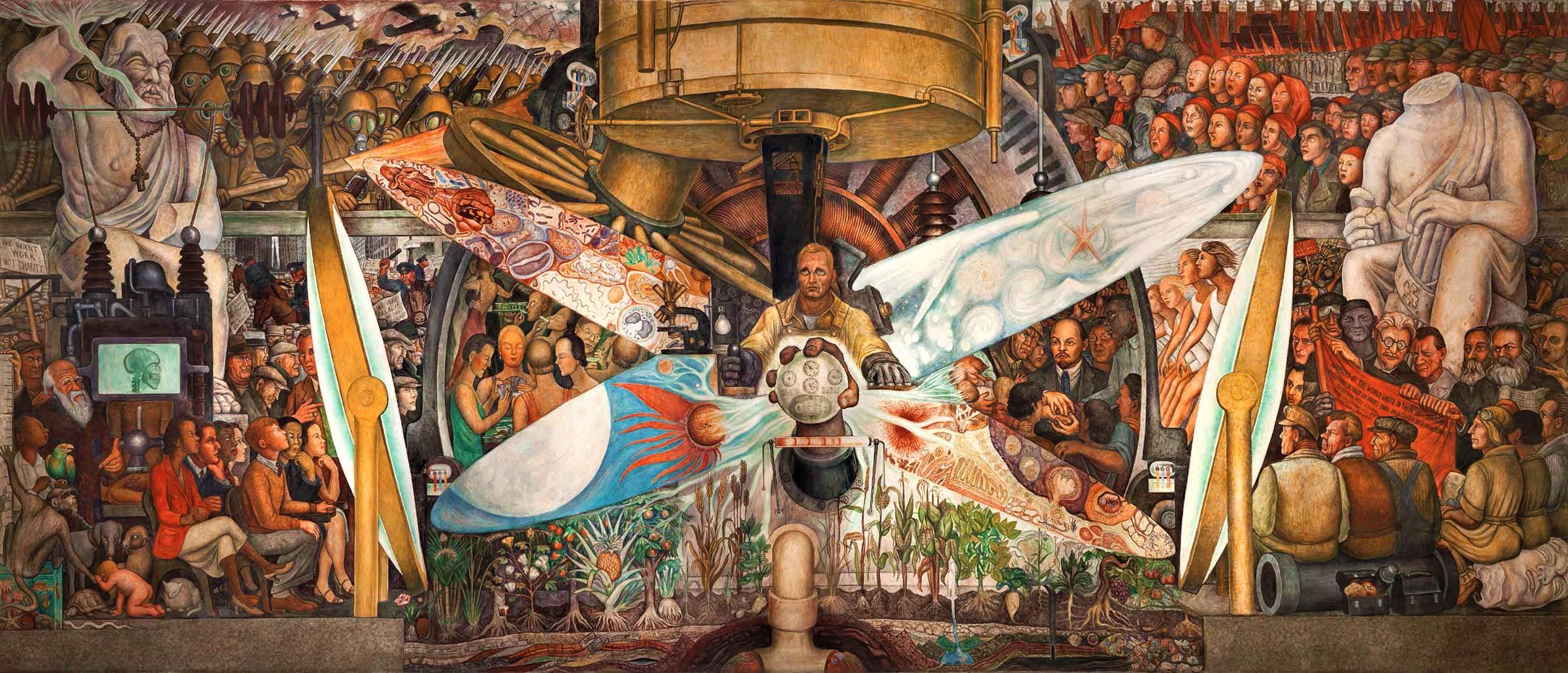

The mural-painting policy gave him the chance to create the enormous monumental paintings which form the most spectacular part of his work. He produced the earliest mural paintings of modern Mexico. His first attempt, the 1922 Creation Allegory for the Bolívar amphitheatre of the University of Mexico’s Preparatory School, painted on wax, not fresco, still showed the academic influence of his early training. Soon though he followed in the footsteps of the fresco painters of the Italian Renaissance and adapted their methods to the themes of modern, post-revolutionary Mexico in its national, historical, and sociological aspects. He had learnt the techniques of fresco-painting in Italy, and from 1923 to 1928 he decorated the Secretariat of State for National Education in that style. To some extent his method was not unlike that used by the Mayas and the Aztecs: he painted in broad bands, one laid above the other, and using no perspective, he created an effect of depth, both in physical space and symbolically in time. He showed workers at their various trades and the poorest peasants, the ‘indios’. With simplified and accessible use of line, with massive and powerful forms and the rich, violent colours of Mexican working-class art, he hoped to invent ‘a monumental and heroic art inspired by the great traditions of prehispanic America’.

For a long time Rivera almost entirely abandoned the easel and in a series of huge frescoes on public buildings he narrated the heroic history of popular uprisings in Mexico. Each scene was designed as a manifesto, a lesson with its explanatory text on a long ribbon, a celebration. Between 1923 and 1928 he produced a cycle of 58 frescoes showing the main events of the revolution for the Secretariat of National Education in Mexico. In 1927 on the walls of the National School of Agriculture in Chapingo he painted compositions in which clothed and unclothed figures celebrated work on the land. One of these was the Benefits of Agriculture which bore the inscription: ‘This establishment teaches exploitation of the land, not of man’. When he was invited to Moscow in 1927 he painted a large fresco for the House of the Red Army. Then in 1929–1930 he decorated the Palace of Cortes in Cuernavaca and the Ministry of Public Health. At various times between 1929 and 1951 he worked on the most ambitious project of his life, the decoration of the stairs and walls of the Mexican National Palace. In 1930–1935 he worked on the first fresco on the main staircase. There he created one of his greatest works, The History of Mexico, from the Conquest to the Future. This was an enormous composition packed with precise details, especially details of pre-Hispanic civilisations which he had researched in Yucatan. All humankind is there, from the indigenous peoples to conquistadors and then on to show the heroes of independence and revolution, with effigies of History, Science, and Philosophy crowning the whole.

From 1936 to 1940 he paused in his immense work at the National Palace in order to concentrate on easel paintings and lithography, producing landscapes and figures, still in celebration of his country and its inhabitants. These were intimist and attractive, often rich in the same vein of poetic folklore which humanises his frescoes. He also painted portraits, sometimes penetrating, sometimes fashionable. Mexico’s entry into the war disturbed him, and after painting some rather Surrealist canvases he returned to the themes inspired by the indigenous inhabitants of his land. In his Woman Selling Flowers he expresses both beauty and sorrow, as lilies in Mexico are a sign of grief, funeral flowers placed on altars on All Souls’ Day.

After 1940 Rivera continued with the final paintings in the National Palace. His militant style became more human and historical, less filled with revolutionary symbolism and more descriptive of Aztec daily life, of which he had now gained an archaeologist’s knowledge. These paintings are less densely constructed, as for instance the El Tajin fresco of 1950. Between 1943 and 1945 or 1949 he painted the frescoes at the National Institute of Cardiology; and in 1947 the moving Sunday Afternoon Dream in Alameda Central Park. Into this picture he introduced the famous Death’s Head in a Hat by José Guadalupe Posada, whom he admired, and a portrait of himself strangely depicted as a child protected by Frida Kahlo, his wife, a Surrealist painter and at the time in ill health. In 1952–1953 he created a relief-mosaic in polychrome tiles, History of Mexican Sports, for the stadium of the University City. In 1955 he produced The History of Medicine for one of the Social Security buildings. He watched the traditional October parade in Moscow in 1956 and then painted the Anniversary Parade of the Russian Revolution. In Mexico he created the Fountain of Tlaloc, an imposing and almost disturbing mass entirely covered with polychrome mosaic in the style of Gaudi which honours Tlaloc, the Aztec rain god, as a homage to the art and civilisation of the original inhabitants of Mexico.